Visual arts

Visual arts

Beauty and audacity

Beauty and audacity: Know My Name presents a new, female story of Australian art

november 16, 2020

Review: Know My Name: Australian Women Artists 1900 to now, National Gallery of Australia

Know My Name is more than an art exhibition, although the exhibition attached to its launch is large, complex and wonderful. Described as a “gender equity initiative”, it is part of a strategy by NGA Director Nick Mitzevich to move towards a culture of inclusion in both collecting and exhibiting.

The exhibition begins with a massed display of portraits, hung like a 19th century salon, almost like an honour guard. The subjects are all people with a purpose.

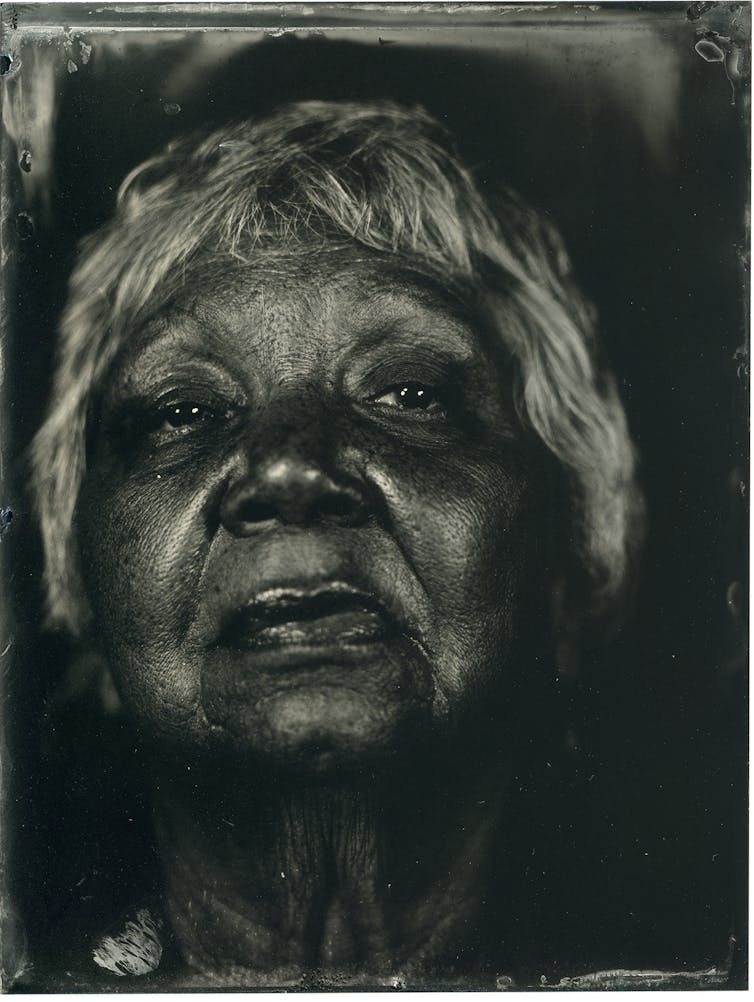

Brenda L. Croft’s intense monochrome portrait of Auntie Matilda House, the Ngambri-Ngunnawal elder, provides a welcome to country. Nearby, Julie Dowling’s iconic, heartbreaking portraits of her family and community’s grief and loss are placed alongside Violet Teague’s Dian Dreams (1909), a painting with a subject who does not need to bask in anyone’s approval.

Some of the works are well known, others less so. Inevitably, the eye is drawn to Grace Cossington Smith’s The Sock Knitter (1915), the work that first placed women artists at the centre of Australia’s art history.

A century before the first Countess Report released its meticulously researched data on the inequitable treatment of women artists, The Sock Knitter was exhibited at the 1915 Royal Art Society of NSW’s annual exhibition. It was ignored, as was the artist, long regarded as a “lady amateur” flower painter.

To register a comment, please login first